Vanity: When Artists and Money Mix

The following is an editorial from Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar. It does not represent the official opinion of WGDR or its licensee, the Goddard College Corporation.

* * *

December 28, 2004

When tender artists and money mix, and companies are outed for their behavior, the results can be vindictiveness. Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar has been quietly experiencing this since September 1998, almost to the day of our third anniversary online. We thought the wave of unpleasantness had ebbed, until we received a cease-and-desist order as a Christmas gift. Read on...

It all began with a composer who took umbrage at K&D's description of his music as 'knotty.' His work -- yes, to us a tad old-school and shopworn -- was broadcast in anticipation of his interview, and we prepared his page with a biography, photo, and music samples. We knew there was going to be a tart exchange coming up, and looked forward to it. Indeed, over the years we'd made similar verbal gestures with the work of Carson Kievman and Paul Moravec and Beth Anderson and Paul Reale and others, but with their good nature, intelligence and articulateness, they created a wonderful show with us, and let their music shine forth and show us up as grumpy toads.

Though we have fun with our guests and their work, and are happy to let our own combined 80 years of accomplished experience as composers slide through the microphones as opinion, the artists energetically defend their work. It's their job, of course, to make the case for their music (something we all must do in this era ignorant of nonpop), and composers have done that brilliantly on K&D for a decade. But this composer decided to hide from the public instead, and demanded his entire presence be eradicated from K&D. We politely complied, after numerous pleas that he hang on and have some fun with us. It was, indeed, our one and only disappointment among the 252 guests whom we've welcomed to join us at the microphones from 1995 through 2004.

About the same time, on the fifth anniversary of the death of the great Frank Zappa, we presented our first annual Golden Bruce Award by outing a vanity nonpop label. Now, there's nothing unethical about vanity labels by nature. Most of the nonpop business is vanity work -- from the MMCs to the Centaurs to the Albanys that are clearly paid for by the artists, through the Poguses and the OODiscs and the LMPs that are volunteer labors of love, to the New Worlds and even the EMIs that are funded by grants and sponsorships and stipends. Sometimes there's a mix of vanity, support from friends and family, grants, and foundation assistance. None of it makes a buck for composers of its own accord.

Self-publishing has a noble history in the face of otherwise powerful, staid interests. Less philosophically, Kalvos paid for publishing his own first CD on Sistrum, and Damian paid for his first release through Albany.

But because most vanity recordings look like any other label, it's nearly impossible to determine if they are indeed vanity projects. Nowhere on their labels is the term 'vanity' found, especially when the cash is private and no public or grant monies are involved. No clue is offered as to the value -- market or artistic -- of the included work.

So it's distasteful to us when an artist can simply purchase not only credibility but also the appellation "modern master" for cold, hard cash. The audience can't know that -- no matter how mediocre or weak that artist might be, or how unjustly such a so-called "modern master" might paint the rest of the composers who are indeed masters but aren't so able to raise a grand a minute for the title -- this is a vanity project, with purchased musicians and for-hire recording labels. Yes, that information is crucial in an era when recordings rather than scores or concerts assign social and artistic significance.

That's what triggered our award. It wasn't the presence of the process, but rather its implications and numerous other exploitive characteristics (as explained in our award essay and on show #169, "Rent-a-Band"). Would that I could get an editor at Time or Rolling Stone to label me a "modern master" for handing over a few thousand bucks. In the public media it would be considered bribery; in the vanity label world, it's what? You choose the term -- how about 'commerce'? 'Tain't art, Bucko. Whatever it is, you can bet our friends at the vanity desk were unhappy to have the curtains pulled back and the light stream in (after which they assumed we'd be slighted to be called "just deejays").

Okay, so what are Kalvos & Damian's problems? Well, we have several, but they are intertwined as one. The licensing agencies didn't know what an Internet was when K&D started online with program excerpts in Real Audio 1.0 -- it was before 'cybercasting' was morphed into 'webcasting', before the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the Mickey Mouse Act, before the CARP panel figured out how to shovel more money into the pockets of its industry buddies and break the backs of renegade producers. That was way back when it meant a risk of knowledge and time and effort and insight, and time taken from our own compositional lives to figure it out and make it happen. We may have been accidental pioneers, but we pioneered nonetheless.

Look, as composers and performers and even publishers ourselves, Kalvos & Damian have done our best to be sensitive to legal and licensing issues.* We operated under broadcasting licenses before the DMCA changed that, and afterwards, began requesting releases from artists and labels for our archived programs. Choosing that or K&D's shutdown, our colleagues were happy to help, and so our filing boxes are filled to bursting with letters of good will and slips of paper using our release text. Composers and performers and labels have stood with us in our mutual hopes and dreams.

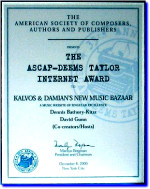

As a volunteer project that started as a small radio program, but which began to grow into a chronicle of contemporary nonpop composition, we felt it important to make the works of our guests available in as much context as possible -- their own words as well as the musical surround in which they were created. This was ambitious and utterly unique for a volunteer project, and ASCAP recognized our contributions with its 2000 ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for Internet Journalism, and in recent weeks our own station WGDR-FM acknowledged our work with its Excellence in Broadcasting Award.

The next thread of the intertwined problem is that from 1998 into the new millennium, we also received attacks from the offended composer of the knotty music, and our telephone conversations with the vanity entrepreneur were fruitless. And, by no mere happenstance, our knotty composer secured a place for his work on the very vanity label that had received our coveted award. Worse than that, though, both were entirely unwilling to go on the record, in public, in the light of day -- because, we suspect, they knew how their positions would be heard by our listeners. The composer, wealthy enough to buy a slot on vanity labels as well as to create his own label and issue recordings of his music, continued attacks on your friendly volunteer composer programmers, attempting to drive a legal wedge between us and WGDR and Goddard College by sending legal documents to them behind our backs.

Throughout, K&D kept the composer's identity private, redacting his name from public correspondence as a courtesy. He was and is a colleague, after all, and Kalvos's very own work appeared with his on (yet another) vanity recording project. Our international Board of Advisors offered counsel to let it be. So by late 2000, both composer and label went back to their pay-for-play work, we continued our composer advocacy project, and the issues were settled.

And so it was with astonishment that we received, two days after Christmas, a cease-and-desist order from a law firm representing those very same two composers affiliated with the vanity project that proclaimed 'modern masters' for cash!

Perhaps our receipt of yet another award triggered some disaffection, disguised as a legal case with threats of $150,000 fines. Or maybe it's the Bush administration mentality that supports media censorship. But this isn't so lofty; it struck us as simple vindictiveness. Though it's hard to be certain reading between the threats, it appears that only our original composer nemesis was involved in sparking this legal skirmish. We wholeheartedly hope this behavior had not become viral, sickening other artists.

Now, what makes the letter funny -- if legal threats can ever be funny -- is the lawyers' mishmash of factual errors:

- They used the incorrect radio station call letters.

- Their claim of 'retransmission ... without permission' demonstrated ignorance of our release system (written for us by a different vanity label, by the way).

- Writing that we 'were contacted in February, 2000 regarding the same matter' -- aside from abusing the poor comma, that is -- they forgot that we had answered immediately and asked the agency to offer their sponsorship of the site as other agencies have done, to which correspondence they did not respond.

- We didn't 'receive taped programs', we produced the show through our own efforts and at our own expense.

- They did not listen, but only read the playlists. And so they didn't discover that the specific H__ pieces they requested to be removed were already gone within days over four years ago. The V__ compositions in the current letter were new requests, and they're gone now, too.

- We made no agreements with Mr. H__ whatsoever.

- They identified 'C__' as composed by either 'Mr. H__ or N__V__.' Huh? Either? They represent them and they don't know who wrote it? Or maybe it was just another 'comma malfunction.'

- Only the male composer deserved an honorific before his name.

Kalvos & Damian love funny things. And were this not a Gilbert & Sullivanesque patter of sinister threats that could vandalize and even shut down an award-winning research site that documents our often-ignored niche of music -- one that has been said of by Tom Johnson, a leading light of musical composition, "a composer not well represented in Kalvos & Damian is nowhere," one that has been called by the New York Times, "An essential resource for fans of new music," and one described by the Village Voice as, "The most important Web site in new music" -- it could be a real knee-slapper.

But it's not. It's not funny, because we know the difference between the argument of making one's case vs. commonplace, street-level, anti-artistic intimidation. (Altering these five shows demanded 15 hours' work that was stolen from other composers.) And these people know who we are, and that we, as their colleagues, reserve the right to criticize them without being victims of what can only feel like thuggery. Were this happening to them, we'd lay odds that they'd be all over the news media screaming censorship. So let's not misrepresent the reality -- we have respected their requests at each step of the way. So now they are attempting to censor opinion which they are unwilling to defend against -- because they cannot.

We welcome a debate, a public one. We always have. We still do. But they have shot from behind the backs of lawyers -- and we have generously offered them anonymity in return. To date, they have offered nothing.

So now we're calling them out, out from hiding, out from behind lawyers, out from $150,000 intimidations.

We say: "Defend your music! Defend your business practices! Defend your terms! Stop hiding yourselves behind 'rights' and demeaning the composers who actually need those few pennies, and start talking about your work! Your ethics! Your quality! Get yourselves into these studios -- we know you can afford the trip -- where you, like everyone else who has appeared on our program, will get a complete, fair, live, unedited chance to show your substance. What are you afraid of? Come on out! Your microphone is on!"

Perhaps they'd actually be proud to go down in the annals of music history as the artists who demolished "the most important Web site in new music" at the very genesis of worldwide-accessible composition. The acrid smell of freshly-lit Molotov cocktails is on the air and the net.

Okay, there's a lesson in here somewhere. One is that taking on a project in unfamiliar territory has dangers of disappointment and failure and risk -- though that's what art is about, I'd hope. Another is that money and power abuse the poor and powerless, but we all know that lesson. It couldn't be that it's all mundane, this little effort to smash K&D? Well, that's not much of a lesson. But then, this isn't much of an exercise, is it?

December 28, 2004

*Okay, you're asking, "Why the hell don't you guys just get this right?" We could turn the question around to "Why the hell don't you use your cellphone right?" And you'd say, "Huh?" And if you were savvy, you'd know what the question meant and you'd say, "How can I predict how the future will regulate what calls I make or pictures I take or videos I shoot or games I play or whatever the hell else the phones will be able to do in another few years?" You could read some Lawrence Lessig, of course, especially The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World.

So voilà, that's what happened with K&D. Here's the long story.

The very few people who were doing any radio show streaming and archiving back in 1995 assumed reasonably that the licensing that covered their broadcast shows covered their online shows. How many listeners could there be? Who knew the future? The Internet was new. Indeed, Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar was one of only 50,000 sites to be found back then. Fifty thousand, and today there are tens of millions. Pioneers then, for those with a sense of history.

But Kalvos himself has been a copyright aficionado for some time, having written some groundbreaking stories about it in the early 1980s, including one in which he quotes Bill Gates as saying "There's nobody making money writing software." Kalvos knew to keep his eyes open and his arms wide.

How times have changed. Not just from Bill's 1980, but from Kalvos's 1995.

As listenership increased, we outgrew the small RealAudio server we had used at Goddard College by early 1996. After some searching, we found a young guy named Mark Cuban (now the multimillionaire owner of the Dallas Mavericks), then the entrepreneur of a small operation called AudioNet. He took us on, and K&D started streaming its archived shows from there in the summer of 1996.

Kalvos soon smelled change in the air. In late 1995, we had already participated in an ad hoc panel at ASCAP on the future of music online. Now, a year later, something else was up -- the discovery, with faster connections, that online music was interesting. And that there might be money in it. And everybody likes the smell of money.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act was being cobbled together by the unknowing and the self-interested. AudioNet saw that coming too, telling us that it looked like there was going to be a problem with on-demand programming that they didn't want to get involved with. They changed their name to Broadcast.com a few years later, and went forth with a new model. We went forth on a server hunt.

K&D had already made sure that we posted shows, not 'songs'. We felt our program wasn't some big new music jukebox, but rather a cohesive arch of shows with commentary, interviews, and context. Breaking it into 'songs' was an alien pop concept. AudioNet remained skittish, and we found ourselves homeless again in 1998. That's when we moved our archive to kalvos.org to supplement the composers pages and other features that had already been there for a year.

It looked like the DMCA was going to support streaming only, and not downloading, so we removed the download options. The kink was that it also looked like corresponding playlists were going to be disallowed -- again, a pop thing, so folks wouldn't cherry-pick the tunes they wanted and leave the rest behind. But what kind of research doesn't document? We kept them.

About that time, we figured some sort of legal release was going to be important. Joseph Celli of OODiscs wrote one up for us, and we started asking for these little slips of paper to release archiving rights for dialup-speed monaural streams -- good taste-testing, but nothing you'd want to keep on your years-yet-in-the-future iPod.

The DMCA went into effect in 1998 and was a kicker, especially since it provided a handsome two years for the Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel to get its act together to determine the licensing rate. We guessed that it would parallel the radio methodology, and figured we could fundraise for a $300-or-so yearly license.

By the beginning of 2000 -- when there were some 240 K&D shows online -- it looked like CARP was ready to set the rates. Nope. It took fully into 2002 for that to happen -- when almost 350 shows were online.

It was then we learned we'd assumed wrong. 'Shows' had no meaning. It was 'songs', and CARP said it was seven cents per 100 listens. And there would be no blanket license. None.

Think of that. Not only was the rate huge (they later reduced it by half for shows like ours), but it required for us an unattainable level of digital 'paperwork' that expected a record of the individual pieces listened to, for how long, and by how many people.

What were the implications? First of all, we had no such records. Because we archived full shows, and did not use a costly RealAudio server, there was no record of how far into each show a listener might have continued. Was it just the essay? Or the full two hours? Did they skip that knotty piece and go for the smooth one? Were they elsewhere and the stream had been left running? Was somebody just trying to jack up their own royalties?

Second, it would be impossible to assemble a volunteer panel to break up the shows (350 of them at the time, representing 700-plus hours of archived audio) into 'songs,' even if that was desirable. And if that by some miracle could have been made to happen, we'd run into the third problem -- that a multi-digit, embedded serial number was to be applied to each 'song' as presented on the CD, and the bulk of K&D's content was either made up of private recordings from composers or was drawn from historical recordings.

That opened up the fourth problem: the releases we'd gotten. What of those composers and labels (almost all of them) who had released their work royalty-free? And the fees -- who would get them? The 'industry', which plowed nothing back into the composers' world, the world where their research and development actually took place? Hardly an attractive thought, as much of K&D's support came from those composers. Imagine a composer paying K&D to pay royalties to pay Britney Spears.

And upon that followed the aesthetic and historical fifth issue: If the shows were broken up into 'songs', what was to prevent listeners from skipping the context and commentary and interviews that were at the very heart of K&D's reason for existence? The absence of song-division enhanced the context for composers seeking an audience, and the baby-bathwater regulations would ruin that immersion.

Not that downloading dialup-speed, monaural streams was likely to dent the composers' or labels' or performers' incomes, but we did take all that into account -- and sighed heavily.

The licensing agencies were actually as cooperative as the composers and labels. They knew that K&D was simply an exception because of its research character, presentation mode, pre-DMCA, pre-CARP historical scope -- being the only program of its kind -- and the lack of grandfathering in the law was an unfortunate omission that hurt us and few others. They looked upon us kindly.

So we continued on the promised path: dialup-speed, monaural streams; composer and label releases; context; and good will. For Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar -- with a long-standing, delicate web of cooperative efforts -- it was an all-or-nothing proposition, and everyone knew it.

Hell, we knew that any wing-nut with a grudge or bureaucrat with an itch could destroy a decade's work. And that might be happening right now.

So then, by mid-2004, we decided the K&D show would be ending. The work had grown burdensome, not least of which was making sure we were on the white-hat side of the increasingly bitter intellectual property debate. The Sonny Bono copyright extension had more folks aroused, and the U.S. participation in the World Intellectual Property Organization treaty rang the death knell for the Commons -- the public domain and the gentle, human agreements among artists and presenters that had served us for over 200 years. (Yes, read Lawrence Lessig again, or maybe a dose of Siva Vaidhyahathan's Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity.)

And so here we are. And I hope that answers that question that we did do it right -- as right as anyone could, without being able to predict the future. (Now don't take my picture with that cellphone, or I'll sue yer ass!)

* * *

The preceding was an editorial from Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar. It did not represent the official opinion of WGDR or its licensee, the Goddard College Corporation.