Composer Profiles

Zeke Hecker

Zeke Hecker

Zeke Hecker

Listen to this show

|

Zeke Hecker

for RealAudio comments by the composer, [not yet available].

for RealAudio comments by the composer, [not yet available].

for RealAudio version of first of Three Waltzes, 1:36/94K.

for RealAudio version of first of Three Waltzes, 1:36/94K.

for TrueSpeech version of first of Three Waltzes, 100K.

for TrueSpeech version of first of Three Waltzes, 100K.

for MPEG-2 audio version of first of Three Waltzes, 375K.

for MPEG-2 audio version of first of Three Waltzes, 375K.

for On Composing for Woodwind Quintet, essay by the composer.

for On Composing for Woodwind Quintet, essay by the composer.

for I Am and Autodidact, essay by the composer.

for I Am and Autodidact, essay by the composer.

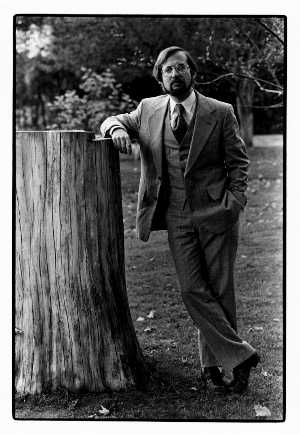

Zeke Hecker was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1947, and attended the Lawrenceville School and Harvard College. Since 1971 he has lived in Guilford, Vermont. Until his retirement in 2004, he taught English at Brattleboro Union High School, where he was local coordinator of the Metropolitan Operaıs School Membership Program. In recent years he has presented teacher workshops at the Met and written study guides to the Met broadcast season for its Web site. He is principal oboist of the Pioneer Valley Symphony and the Windham Orchestra, co-founder of Friends of Music at Guilford, and a former director of the Consortium of Vermont Composers. He is currently president of the board of trustees of the Pioneer Valley Symphony. His wife, Linda, is Assistant Director of Educational Services for the Institute for Research and Training at Landmark College, as well as a violinist and violist. Their daughter, Anna, is a writer living in New York.

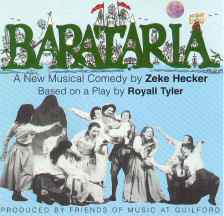

Primarily self-taught as a composer, Zeke Hecker has written over 120 works, including the operas "Mushrooms," "Kafka Quintet," and "Pericles, Prince of Tyre" (based on the Shakespeare play); the musical comedy "Barataria," based on a play by the 19th century Vermont writer Royall Tyler; "My Last Duchess" and "Landscapes", both for voice and orchestra; "Icebreaker", "The Birthmark", and "Elijah Variations", for orchestra; incidental music for plays and films; chamber music, mainly for woodwinds; numerous songs and song cycles.

His works have been performed by the aforementioned musical organizations as well as the Sage City Symphony, Vermont Philharmonic, Thayer Symphony, Carson City Chamber Orchestra, Craftsbury Chamber Players, Vermont Contemporary Music Ensemble, Constitution Brass Quintet, Central Vermont Brass Quintet, Ohio Brass, TrioWest, Laredo/Robinson Duo, and Hale/Goodrich Duo, and have been heard at the Warebrook Festival of Contemporary Music, the Yellow Barn Music Festival, and in Barcelona on a program devoted to works by American composers. They have been broadcast on Vermont and Massachusetts Public Radio and Dartmouth College Radio. His "Trio for Oboe, Clarinet, and Bassoon," published by Trillenium Music Company, is in the current repertory of several ensembles. "Six Waltzes for Piano" were choreographed by Kathleen Keller for the ballet "Degas." "Mushrooms" has been staged three times, most recently in London in 1999. A suite from "The Tempest", conducted by Blanche Moyse, was featured on the soundtrack of the award-winning documentary film "The Stuff of Dreams," which has been shown on PBS television. He has received grants from the Vermont Arts Council, the New England Foundation for the Arts, and Meet the Composer.

Zeke Heckerıs works from recent years include a viola sonata, a flute sonata, and a partita for brass quintet , but most are for the theater. "Barataria," composed 1995-8, received its stage premiere in April 1998 in Putney, Vermont. Several songs from his musical play "Tryst" (1998-1999) were performed in spring 2002 in Brattleboro on a program devoted to American Musical Theater, and the Vermont Theatre Company successfully staged his musical "Double Exposure" in 2003 ("a wonderful blend of clever wordsmithing married to just the right melodies -- melodies that you can hum and sing the words to ... the lyrics weave through the melody effortlessly," wrote William Menezes in the Brattleboro Reformer).

Spring 2005 was a busy season. At the beginning of May the Vermont Theatre Company staged his newest musical comedy, "Bemused," again to critical acclaim ("an instant local hit" ... "a showcase for Heckerıs acrobatic use of language" ... a "memorable" score). Later in the month the Windham Orchestra and the Brattleboro School of Dance revived his ballet "The Unhappy Kingdom," which had been premiered in March for school audiences. On June 18th the Amato Opera in New York City gave the premiere of his opera for children, "The Forest," which the company commissioned. For these works Hecker has written libretto and lyrics as well as music. September 2005 saw the premieres of his "Guilford Festival Overture" for chamber orchestra at that eponymous event, and of the sonata for flute and piano at Dartmouth. His First Symphony, commissioned by the Pioneer Valley Symphony, received its premiere in February 2006. Several more musicals are in preparation, including "Things To Do," scheduled by the Vermont Theatre Company for its 2007-8 season.

Short Bio

Zeke Hecker was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1947, and attended the Lawrenceville School and Harvard College. He lives in Guilford, Vermont, and taught English at Brattleboro Union High School from 1971 until his retirement in 2004. A coordinator of the Met School Membership Program, he writes online study guides for the Metropolitan Opera website and leads teacher workshops at the Met. He is principal oboist of the Pioneer Valley Symphony and the Windham Orchestra, co-founder of Friends of Music at Guilford, and a former director of the Consortium of Vermont Composers.

Hecker has composed over 120 works, including operas, orchestral pieces, chamber and choral music, incidental music for plays and films, and songs. His music has been performed by orchestras, chamber groups, and choruses in New England as well as in Barcelona and London, where his chamber opera "Mushrooms" was produced in 1999. The opera "Pericles, Prince of Tyre" (from Shakespeareıs play) was staged in 1981, and the musical "Barataria" (based on a play by 19th century Vermont playwright Royall Tyler) in 1988. "Six Waltzes for Piano" were choreographed by Kathleen Keller in 1997 for the ballet "Degas." A suite from "The Tempest," conducted by Blanche Moyse, was featured on the soundtrack of the award-winning documentary film "The Stuff of Dreams," which has been shown on PBS television. He has received grants from the Vermont Arts Council, New England Foundation for the Arts, and Meet the Composer.

Recent works include the musical comedies "Double Exposure" and "Bemused," for which he wrote book, music, and lyrics; these were staged by the Vermont Theatre Company in 2003 and 2005, respectively. His ballet for children, "The Unhappy Kingdom," was given in spring 2005 by the Windham Orchestra and the Brattleboro School of Dance, and his childrenıs opera "The Forest" was staged that June by the Amato Opera in New York. Recently came two more premieres: a sonata for flute and piano (November 2005, Dartmouth College, performed by Alex Ogle and Susan Dedell), and Symphony #1 (February 2006, Smith College, Pioneer Valley Symphony conducted by Paul Phillips).

Zekeıs wife Linda, a violinist and violist, is assistant director of the Landmark College Institute for Research and Training. Their daughter Anna is a writer living in New York City.

Representative musical compositions:

Orchestra

- "Icebreaker" (1978)

- Variations on "Elijah the Prophet" (1988)

- "The Birthmark" (1989)

- Guilford Festival Overture (2005)

- Symphony #1 (2005)

Voice with Orchestra

- "Landscapes" (1976): six songs to poems of Jenny Stewart for mezzo-soprano and strings

- Two Scenes from "Dracula" (1984) for soprano, tenor, baritone, and strings

- "My Last Duchess" (1985) for bass-baritone, strings, double brass choir, and bells

Chorus

- "Hallelujah" (1973) for SATB a cappella

- "Three Madrigals to Poems by Robert Herrick" (1999) for SATB a cappella

- "Animal Lullabies" (2000): Five Songs to Poems of Jane Yolen for SSATB a cappella

- "The Masque of Amazons" from "Timon of Athens" (2005) for SSATB a cappella

Incidental Music (for chamber ensembles)

- "A Midsummer Nightıs Dream" (1975)

- "Antigone" (1976)

- "The Tempest" (1977); also arranged for orchestra

- "The Taming of the Shrew" (1979)

- "The Uninvited Pest" (1985): music for a cartoon film, for woodwind quintet

- "Macbeth" (1986)

Chamber and Solo

- Passacaglia, Adagio, and Fugue on a Theme by Jimi Hendrix for woodwind quintet (1990)

- Trio for Oboe, Clarinet, and Bassoon (1990)

- "The Weather Forecast": Theme and Six Meteorological Variations for Violin and Cello (1990)

- "3X5": Three Miniatures for Brass Quintet (1991)

- "The Elements" for Flute and Harp (1992)

- Six Waltzes for Piano (1992)

- String Quartet in D "Palindromic" (1997)

- Sonata for Viola and Piano (2002)

- "Quotidian" for Woodwind Quintet (2002)

- Sonata for Flute and Piano (2004)

- Partita for Organ (2004)

- Partita for Brass Quintet (2005)

- Trio for Flute, Clarinet, and Bassoon (2006)

Song Cycles (voice and piano)

- Five Songs from "A Bad Childıs Book of Beasts" (Belloc) (1973)

- Three Yeats Songs (1973, revised 2006)

- "Songs of Antigone": nine dramatic monologues based on the play by Sophocles to poems by Betsy Snow Hickok (1982)

- "Crosscut": Four Songs to poems by Alicia Hokanson (1986)

- "A Cycle for Cynics": 13 songs for baritone and piano to poems by Ambrose Bierce (1990)

- "Except the Moon": Five Songs to poems by Meg OıConnell (1991)

- "Rough Eden": Three erotic lyrics to poems by Amy Thomas (1993)

- Other cycles and individual songs to poems by cummings, Donne, Frost, Auden, Tzu Yeh, Heine, Hecker, and others

Opera and Ballet

- "Mushrooms" (1978): chamber opera in three scenes for soprano, baritone, and woodwind quintet

- "Pericles, Prince of Tyre" (1980): opera in three acts from the play by Shakespeare

- "Kafka Quintet" (1994): chamber opera in five parts on stories and sketches by Franz Kafka, for tenor, baritone, and brass quintet

- "The Forest" (2003): opera for children based on a story by the Brothers Grimm, for adult and children soloists, childrenıs chorus, and piano

- "The Unhappy Kingdom" (2005): musical fable for orchestra, dancers, and narrator (story by the composer)

Musical Theater

- "Barataria": a musical comedy (1997). Original play and lyrics by Royall Tyler. Additional lyrics by the composer. Soloists, chorus, dancers, and orchestra

- "Tryst": an adult(erous) musical (1999). Book, lyrics, and music by Zeke Hecker. Four actors (two men, two women) and piano

- "Double Exposure": a musical play (2003). Book, lyrics, and music by Zeke Hecker. Two actors (one man, one woman) and piano

- "Bemused": a musical comedy (2004). Book, lyrics, and music by Zeke Hecker. Four actors (one man, three women) and piano

Arrangements

- Five Rueckert Lieder (1986): songs of Mahler arranged for mezzo-soprano and woodwind quintet, in the original keys.

An autobiography originally published in Consorting, newsletter of the Consortium of Vermont Composers:

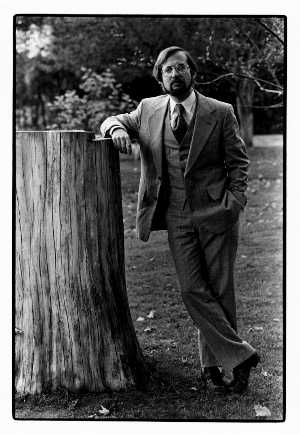

Zeke visits K&D in 2004

Zeke visits K&D in 2004

One of my inspirations to begin composing was Don McLean, former schoolmate and current neighbor. The first music of his I heard -- clean, unpretentious, witty -- made me realize that a composer doesn't have to be a conservatory graduate. If Don could do it, so could I. America has a healthy tradition of demystifying music. Think of William Billings and the other colonial psalmodists, of Otto Luening and his Bennington progeny, of Gershwin the autodidact. (A character in a Vonnegut novel asks an artist, "Self-taught?" to which the artist responds, "Isn't everybody?")

I have no formal musical training beyond a few years each of clarinet and oboe lessons and a few weeks of counterpoint. Everything I know has come from playing in orchestras, chamber groups, and theater pits; from listening to records and broadcasts; from reading the back of record jackets. I recommend all these activities. But I still regret missing the formal study. Writing music is hard, slow work for me. (When Richard Strauss was told that Pfitzner agonized over every note while composing, the facile Strauss replied, "Then why does he bother?")

Until recently most of my works have been vocal: "art" song, orchestral songs, operas. There have also been a few short choral works, some chamber music (mostly for woodwinds), and lots of incidental music for plays. The perspicacious reader will notice unmistakable traces of the unschooled composer: preoccupation with short forms, avoidance of abstract ones like fugue and sonata. At least a poem or a play interlude suggests its own musical character, so I don't have to invent one.

The stress on vocal music is partly a crusade. Among musicians, the English language has a bum rap. Even English-speaking critics and performers still call it unsingable (as though German, with its contorted umlauts and collision-course consonants, were somehow superior). As a student and teacher of literature, I began writing music intending to set American and English texts as naturally as possible, to make them singable (and intelligible) by following the natural tempos, rhythms, and inflections of the language. Usually I take Ned Rorem's example: one note to each syllable and no repetitions unsanctioned by the text.

Extremes of vocal range may be thrilling, but I avoid them if the words will be lost. (I really hate the contemporary trend towards stratospheric soprano tessitura.) My favorite voices are mezzo-soprano and baritone, the ones that come closest to the sound of speech.

As for the widely held notion that only second-rate literature can be ennobled by music: why spend endless hours turning bad poetry into song? I take texts from the best writers I can find, living or dead. If I can collaborate directly with a like-minded writer, so much the better.

After a while the pieces I wrote began getting longer and fatter. I built up to orchestral writing gradually: strings only, then classical orchestra with paired winds, now full orchestra with its embarrassment of riches. Luckily, I have had a kind of training for this: three decades of playing in orchestras in front of the wind section (best seat in the house) where I can watch everyone sweat and hear all manner of ways to mix instruments together. Maybe it's the result of those galley years, but my main principle of orchestration is to give each player something interesting to do, instead of treating instruments as aural ballast. Happy players perform better than makework drudges.

(My opera Pericles, a setting of the Shakespeare play, requires a twelve-piece orchestra: string quintet, wind quintet, trumpet and percussion. When the opera was staged in Brattleboro in 1981, it received two reviews. One, from New Hampshire, called the orchestration "thin". The Brattleboro Reformer's critic said that the "rich" orchestration made the ensemble sound Wagnerian in proportion. In accordance, then, with the Three Bears theory of asesthetic criticism, I guess it was just right.)

There has never been a professional performance of my music -- which is, I suppose, only appropriate, since I'm an amateur composer. But most of my works have been performed, because they've been written for specific performers or occasions, almost always local: high school groups, theater companies, community orchestras. I like it that way. I would certainly welcome a professional performance or two, but at what price? The very notion of competitions is odious, and randomly sending material to musicians of established reputation is like throwing it at a black hole.

The best way to get your music performed is to produce your own concerts. That's partly what Friends of Music at Guilford is -- an outlet for local composers. Every town should have one. If it weren't for FOMAG and a couple of kindred organizations, I doubt that I would have written much music. Now I'm hooked.

Barataria

Barataria

Back in the day...

Zeke Hecker

Zeke Hecker

To reach the composer:

On line: zekehecker@mac.com

By telephone: 1-802-257-1028

By physical mail: 2450 Packer Corners Road, Guilford, Vermont 05301

Zeke Hecker

Zeke Hecker

Zeke visits K&D in 2004

Zeke visits K&D in 2004 Barataria

Barataria Zeke Hecker

Zeke Hecker