Composer Profiles

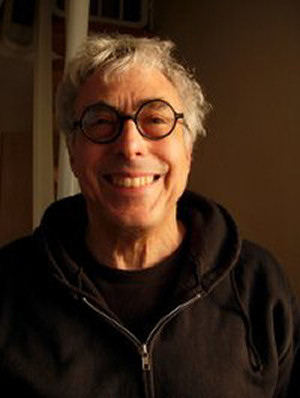

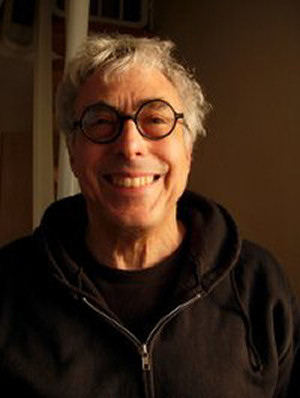

Jon Appleton

has his own home page

Listen to this show

|

for RealAudio 5 comments by the composer, 4:29. In RA 14.4

for RealAudio 5 comments by the composer, 4:29. In RA 14.4

for MP3 streaming version of Newark Airport Rock 1969, 2:12

for MP3 streaming version of Newark Airport Rock 1969, 2:12

for RealAudio 3 stereo version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for RealAudio 3 stereo version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for RealAudio 3 mono version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for RealAudio 3 mono version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for RealAudio 2 mono version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for RealAudio 2 mono version of Newark Airport Rock 1969

for MP3 streaming version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996, 3:23

for MP3 streaming version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996, 3:23

for RealAudio 3 stereo version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

for RealAudio 3 stereo version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

for RealAudio 3 mono version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

for RealAudio 3 mono version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

for RealAudio 2 mono version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

for RealAudio 2 mono version of San Francisco Airport Rock 1996

to reach his page.

to reach his page.

From his page

Jon Appleton

My father was born in Moldavia in 1900 but escaped the pogroms with his family and settled in the Jewish ghetto on Ludlow Street on the lower eastside of Manhattan. Self educated, he became a writer and changed his name from Chaim Eppel Boim to Charles Leonard Appleton. My mother, Helen Florence Jacobs, was born in Philadelphia in1907. She was remarkably beautiful, well read and mercurial.

My parents met at an artist colony near Croton on the Hudson River, founded by a wealthy developer named Colonel Clifford B. Harmon. They were young, idealistic and consumed with a desire to set the crumbling world of the 1930’s on a better track. Radical politics was their aphrodisiac. Membership in the communist party was their extended family.

Unfortunately, like many, sincere, would-be saviors of the world, my parents were better at dealing with the plight of humanity than with the daily and less prosaic needs of a family. Soon after their marriage and the birth of my older brother in 1932, they made the long trek across an impoverished America to Los Angeles. They were lucky and found work in the film industry, my mother as a film editor for MGM. She was also Secretary of The Communist Party of Los Angeles. She was proud to have worked on the Oscar winning film the Best Years of Our Lives and “Action in the North Atlantic , written by my actual namesake, John Howard Lawson.

My father was a writer for 20th Century Fox. His most notable work—at least the only one I know of—was a story for a script for a movie called Lucky Jordan.

The years living in Beverly Hills were not the best years of my parents’ lives. Their marriage deteriorated and they drifted apart. My father stopped seeing his close friends from the old leftist circles in New York, used his middle name as his last, and dropped out of sight politically. Since he never really wanted “a family” to begin with, my birth in 1939 only exasperated the situation. Finally, when my brother tried to hang himself from the stairwell my father left and I never saw him again. For two years my mother tried to cope as a single parent with two children and two jobs. In 1941 she placed me in an orphanage called Mrs. Bell’s. My older brother was sent off to Palomar Military Academy where I joined him two years later. My first real memory is standing in a crib looking out the orphanage window into the hot, bright emptiness of the LA cityscape and wondering where my mother was.

Utopian, intellectually focused, self-absorbed parents aren’t the most nurturing people in the world. They had a way of making one feel like a burden. My mother, however, seems to have planted some seed in me that makes me champion the underdog and bridle against social injustice. She raised my brother and I to stand on our own and never count on anybody. We both held jobs since we were ten years old and tended to excel at whatever we took on. But unfortunately we found it difficult trusting other people.

In 1945, when I was six years old my mother married a wonderful Russian musician named Alexander Walden, neè Bomstein. We called him Sasha. He insisted that my brother and I be taken out of the military academy and that we all be reunited as a family. I love him most, however, for opening my door to the world of music. He was quick to observe the effect sound had on me. Even the simplest tune would set me off singing and dancing. When I moved to Sasha’s house on Gower Street in Hollywood, he made sure that I had my own radio. Every night I would stretch out in bed and listen to the classical music station KFAC until it closed with Fauré’s “Pavanne.” My parents knew that I wasn’t asleep but thought the music would calm me. Little did they know that it had the opposite effect. Some days Sasha would allow me to sort through and play his absorbing collection of 78 recordings: Scarlatti, Prokofiev, Russian folk songs, etc. It was at age six that I began to study the piano.

Sasha was Born in Ufa. He fought with the Red Army until the anti-Semitism drove his family to Shanghai were they became part of a thriving Russian/Jewish community. There he lay down his gun and took up the violin. In 1925 they immigrated to New York City. While he always thought the Soviet Union was the future, I think his loyalty was basically a form of national loyalty for Mother Russia that is deep in the soul of every émigré.

My brother, for some unknown reason, became a physician. For me, however, there was one choice. Sasha was a professional musician so it seemed natural that I would be one too. I dreamed of being either a ballet dancer or a composer. By the age of ten I had written the score and words for a musical comedy called "The Following Lover." I followed this up with a long piece for piano called "The Martian Concerto" which sounded like a simpler version of the last movement of the Prokofiev’s 3rd Piano Concerto.

As a boy I had a beautiful, soprano voice. Shortly before puberty and the American angst of adolescence, I secretly auditioned for the Columbus Boy's Choir. My parents did not want me to leave Los Angeles. To everyone’s surprise, however, I was accepted and sent off to their school in Princeton, New Jersey. After a year of singing ethereal music, my voice began to change and I was summarily sent back to Los Angeles.

I returned to a very anxious and despondent home. Sasha was summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee and immediately fired from his job in the Universal Studio orchestra. My mother was also blacklisted and found it difficult to find any work in the film industry. One evening--I must have been about thirteen--I ran away from home and hitchhiked across the United States. Free of the anger and remorse of home, I was amazed at how exciting the rest of the world was. Of course it had its ugliness. The horrible demeaning effects of segregation were everywhere. On the whole, however, people were exceptionally generous and kind to me. As I passed through the neat, nameless towns and cities, I wondered if I would ever find a “normal” family that would like me to be their son?

Some weeks later I arrived in New York City where a kindly uncle took me in. He was a set designer and an officer in the Scenic Artists Union. What was most astounding about him was his fantastic sense of humor and the total freedom he gave me. I spent the next six months exploring that great city. I remember it as not so different than it is today. The sounds of the City would suggest music to me. A car horn would remind me of the opening of Tchaikowsky’s first piano concerto. Dawn coming up over Brooklyn, casting a blood red glow onto the early morning streets, would remind me of the opening of "Le Sacre du Printemps." Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto made me feel like flying from the peaks of the skyscrapers. Sometimes I would imagine the coos of the doves in Central Park providing a rhythm over which I could sing. The high point of this adolescent adventure, however, was hearing Valdimir Horowitz play his arrangement of the “Stars and Stripes Forever” at Lewisohn Stadium.

While kindhearted, my uncle was not wealthy. I found two jobs. The first was as a "copy boy" at The New York Times. Rushing around the newsroom with teletype dispatches suited my unquenchable nervous energy. The second was as a stock boy at Macy's Department Store. After four months I left my uncle and camped out in one of the stock rooms where I secretly slept overnight in a fortress made up of dress boxes stacked to the ceiling. I had become friends with the night guard who sat outside the employee entrance. In the evenings, after leaving work at the newspaper, he would let me in and before going to sleep I would compose music at the pianos in the Macy's showroom. One morning, with very little sleep, I was struck by a car on 34th Street and was admitted to Bellevue Hospital and soon found my self back in Los Angeles. It was a homecoming from hell.

Following in the footsteps of a painter—no, not a musician—I headed for the South Pacific. If it worked for Paul Gauguin, why wouldn’t it work for me?

The year I spent living in 'Utelei, a village in the northern islands of the Kingdom of Tongan, took me and my music in a new direction. I was sitting on the floor of a grass hut, surrounded by crying infants, being tormented by mosquitoes and trying to understand the old men who were talking all at once. The women brought us food. The sound of the pounding surf down on the beach mixed with the rumblings of a coming storm. It was a signature sound of the first creation. I wanted to capture it all. I was carting around an old Ampex, single-track recorder with loudspeaker attached. Finding power sources was always a problem. That evening I decided to play them back what I recorded. It was almost as good as showing someone a photo of themselves for the first time. Watching their shifting expression I realized that they and their reactions were part of this strange performance developing around and out of me. From that moment my whole concept of an audience changed from passive receptors to active participants in the unfolding work.

I was nearly forced to leave the tape recorder in Tonga because of my need for a sudden departure. Things were getting too complicated and I was forgetting my place in their society. I would return years later to develop a more cordial and mature relationship with the Royal Family. But at that time I had fallen in love with Princess Melanite, the daughter of King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV and was about to be forcibly deported. Providentially, Adrian "Ponto" Bywater Lutman III, an old New Zealand radio operator working in Tonga took me on board his thirty-foot sloop. To everyone’s relief, we sailed for French Polynesia. It took us six purposefully, perfect, desultory weeks to reach Hiva 'Oa in the Marquises Islands (where Paul Gauguin and Jacques Brel are buried). The Ampex was still working and I recorded the chanting in the small Catholic Church and the singing and dancing during the following feast given in our honor.

Ten years later, while living in Bourges, France, I used these recordings to capture my time in those twilight island cultures and fold it into the present. I shaped the piece called “Otahiti.” It was my plan to produce this piece using the sophisticated equipment at the studio of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales in Paris where I had just begun a course taught by Pierre Schaeffer. I was arrested, however, in a demonstration against French nuclear testing in Polynesia. My friend Francois Bayle suggested I lay low in Bourges, a provincial town two hours south of Paris. Even there, I found it a luxury to work with multiple tape recorders, a mixer, audio oscillators, filters and other sound modifying devices which could all be patched together. This arrangement, which later became known, as the "classical studio" for electronic music, was no more or less difficult to use than today’s popular software. The possibilities were fewer but this forced me to think very carefully about both the sonic and dramatic content of my music.

There was a brief hiatus in my composing when I lived in London. My roommate, the experimental composer Dirk Rodney, tried to convince me to become an actor. Dirk introduced me to the playwright Joseph Losey, who cast me in the role of Dr. Benjamin in his revival of Clifford Odet's play “Waiting for Lefty.” The character of Edna was played by the Swedish actress Viveca Lindfors. Unfortunately, the play ran for only nine performances.

Fortunately, during rehearsals, I had met Viveca’s twenty-two year old son, Magnus. We were immediately attracted to each other and fell in love. After the play closed we went to live in Rätvik, a small rural town in Dalarna. It was a magical summer. I spent my days recording the local musicians at the spelmanstämma folk festivals throughout the valley. I was now working with small, portable Uher tape recorder. What fascinated me most was the keyed fiddle that forms the basis for the my piece “Nyckelharpen Variations.” Despite the idyllic surroundings, I began to feel like a prisoner in Rätvik. Aside from my Uher there was no equipment to create my type of music. Magnus spent his days orienteering or splitting wood. In the evenings would we improvise violin and piano duets. Sometimes we went to folk dances where I became quite good at the hambo.

One afternoon I went off to a concert in Stockholm at the Museum of Modern Art. There I met a group of pioneering young composers my own age: Lars-Gunnar Bodin, Sten Hanson and Bengt-Emil Johnson. They were experimenting making music with spoken texts. After listening to some of my early works they warmly accepted me into their group. Through their connections with the Swedish Radio, I obtained a commission to do a broadcast piece called “Dr. Quisling in Stockholm.” The work was an audio biography of the Norwegian composer Knut Wiggen who worked in Stockholm. Earlier, he had convinced the Swedish government to build the mammoth electronic music studio at Kungsgatan 8. He disapproved of the project and refused to let any of our group work there. Years later, I temporarily became its director. For a most unusual reason, it was very difficult to compose this piece. I was accustomed to using the necessary equipment without any assistance. This stage of my work is always very personal. At the Swedish Radio, I was assigned a team of audio engineers. Under my direction, they set up the microphones in a gångtunnel in downtown Stockholm. They mixed the sounds in the most modern studio. I, however, was not even permitted to splice tape. All could do was watch and tell them what to do like some castrated director.

During my first years in Stockholm I lived outside the city on the island of Lidingö. My house belonged to the great Swedish sculptor Bjorn Erling Evensen. The setting on the shore of the archipelago was spectacular even during the artic winter. I was taking care of Bjorn's daughter Micka, then fifteen years old. While we were skiing in the woods, I met a young farmer and poet named John Mellquist . As I recorded John reciting his verse it struck me that I should compose a piece of music illustrating his poem entitled “Kackerlackas.” I called the composition “Scene Unobserved. ” It was a story about what goes on in the forest when nobody is there. I soon discovered that nobody understood the program. Therefore, I decided to turn it into my first film. It was a Bergman like kaleidoscopic, montage of images in a forest where objects, and people, magically appear and disappear even though the forest setting never changes. This black and white film was quite popular but never made it out of Sweden.

Back in Stockholm I developed a promising friendship with the choreographer Suzanne Valentine. We decided to share an apartment together when she introduced me to a young Japanese dancer, Aki Nakamura. Aki was the son of a hockey coach in Nara, the ancient capitol of Japan. Though forced to play hockey by his father, he always dreamed of being a dancer. When Suzanne came to Osaka for a performance, he begged her to let him join her company. By the time Aki and I fell in love, he was ready to return to Japan.

I knew nothing about Japan except the images propagated by the Americans during World War II. What a surprise it was to discover Tokyo and the Japanese. Dressed in a suit and tie, with a briefcase filled with tapes of my electronic music, I marched to the studios of NHK Radio and announced that I had come to work there as a composer. I must have appeared to them as an alien, but so smitten were they by the European and American avant-garde, they agreed to let me in. They asked me to compose music for a children's program. One of the shows was The Bremen Town Musicians, an excerpt of which you can hear on this recording. The piece was made entirely from the sounds of Japanese children playing toy instruments.

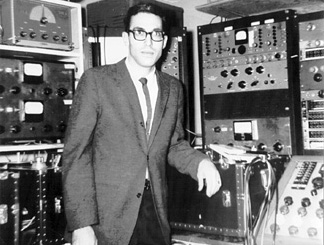

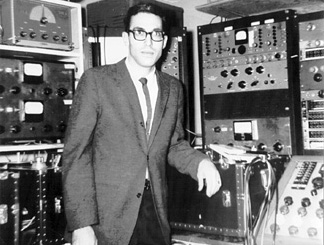

A fortuitous meeting in Japan once again changed the direction of my musical career. At a yakitori bar in Hamamatsu I met two entrepreneurial engineers from Vermont, Sydney Alonso and Cameron Jones. They had just designed and built a digital oscillator bank controlled by a mini-computer. They wanted to turn this into the world’s first digital performance instrument. It would ultimately become the Synclavier. Alonso and Jones founded a company in a depressed Vermont town called White River Junction that had once been the railroad center of northern New England Their nascent company, New England Digital, already had thirteen orders but no instruments. At the time, I was questioning how electro-acoustic music, heard only on loudspeakers, could reach a larger audience. I wanted to do something more direct. When they asked me to join them in Vermont, I jumped at the chance.

I began to compose music that would show of the capabilities of the Synclaiver. As there was only one instrument, I had to come to their small factory in the middle of the night and compose until the engineers arrived at eight in the morning. The size and complexity of the Synclavier increased logarithmically, as did its popularity among more and more commercial musicians and recording studios. It was quite exciting when new functions like "sampling" appeared and I could play any kind of sound on the keyboard. Being a pianist helped, but there was a steep learning curve to access the hundreds of buttons rapidly in a performance situation. Most of the pieces I composed for the instrument sounded keyboard based because indeed I was playing a keyboard. I lugged the two hundred pound instrument on tour across Europe, Asia and around the United States, always playing my own music. I learned two things from this effort. First, I prefer composing new pieces to performing older ones over and over. Second, to my dismay, I discovered that half the audiences came to marvel at the technology rather than hear my music. When I told Leon Theremin this at our meeting in Moscow in 1991, he said it was the same reason so few composers wrote for his instrument the Theremin.

I felt that the best pieces I composed using the Synclavier were Brush Canyon and Homenaje a Milanés. The latter was based on a song by my favorite singer/songwriter, Pablo Milanés whom I had met at one of my Synclavier concerts at the Casa de las Americas in Havana, Cuba. Stupidly, I forgot to record many of pieces composed for the Synclavier, especially the improvisations. Fortuitously, the composer Mary Roberts had recorded a concert I gave in Moscow, Idaho. She sent me a cassette with several of the pieces I had performed in the late 1980s including A Swedish Love Song and Bombay.

Ultimately, touring was exhausting. My fees hardly covered the cost and the Synclavier seemed to get heavier with each flight. It was a joyous occasion when I returned to Vermont after each tour. I had come to love the peaceful nature of the countryside and the changing seasons. I became friends with the visual artist Beryl Korot and composer Steve Reich with whom I often hiked the Appalachian Trail. There is a small college called Dartmouth near White River Junction, Vermont. They had some "cutting edge" composers there such as Christian Wolff and Larry Polansky and it was on that campus, in 1989, that I met the late Russian singer and choral conductor Dmitri Pokrovsky. He brought back into my life all that I loved about Russian language, culture and music. His sense of humor and way of moving reminded me of my beloved step-father Sasha who died in 1981.

I had played a Synclavier concert in Moscow in 1984 at the Composer's Union and it seemed quite sedate. The Moscow that Pokrovsky showed me in 1991, however, was like America's Wild West. Communism was dead and people were filled with hope. I met many young, idealistic composers intoxicated with their new creative freedom. The attitudes of the composition students at the Moscow Conservatory were parallel to the feelings Debussy, Ives and Stravinsky experienced during the first two decades of the 20th century. Daily life was difficult but the life of the mind and the love of music were nurtured in reaction to the repressive political system that was finally beaten down. Yes, Moscow is still drab and the rest of Russia even more so, but hearts and minds of ordinary Russian people are as beautiful as one can imagine. Their intense curiosity and understanding of my music was quite extraordinary. Still, my Russian was weak and eventually I returned to Vermont. I now live in an old farmhouse built in 1785.

In White River Junction, Vermont I fell in with a group of Russian artists who moved to Vermont following Stalin's death in 1952. Boris Budsdarovia, a cook at the Polka Dot Diner, had been a well known songwriter. Alexander Kalishnakov, who had a small studio and taught music to children, had been a world-class pianist. Misha Nijinsky, the nephew of the famous dancer and once a Bolshoi Ballet star, had become an automobile mechanic. Finally, there was Olga Pertsovka who had been the conductor of the Ekaterineburg Symphony Orchestra and was now an assistant curator to David Fairbanks Ford, the Director of the Main Street Museum. They were the subject of several documentaries by the filmmaker Matt Bucy. The best of these films, in which I appear as the interviewer, was Moscow Meat. This documentary won an award at the Bienal do São Paulo. Being with these Russian refugees assuaged my thirst for Russia.

At the Bienal, I encountered the spectacular singer/ethnographer Marlui Miranda, famous for her musical work with isolated tribes in the Amazon. We launched a project called Orphaneus. I composed the songs that she sang with the children from nine Brazilian orphanages. I went with her to visit the orphanages in Salvador, Belém, Olinda, Rio de Janeiro. At first, I had was hesitant about visiting these orphanages. I thought that the experience would be too painful, reminding me of my first six years in Los Angeles. The children, however, were so resilient and full of life that it I found it uplifting. Back in São Paulo Marllui and I composed our first piece together, Filhos da Nana.

Sometimes I dream about living with Marlui in a village in the Amazon but for now, at least, I am back in Vermont.

Jon Appleton

September, 2002

Contes de la Mémoire

Contes de la Mémoire

Appleton & Treu

Appleton & Treu

Contes de la Mémoire

Contes de la Mémoire Appleton & Treu

Appleton & Treu